2 reasons why the Sino-US Dialogue did not focus on the value of RMB

By Nathan Chow Hung Lai (周洪禮)The fifth China-US Strategic and Economic Dialogue concluded on 11 July. Unlike previous meetings, the emphasis was not on the value of the renminbi (RMB). There seem to be two reasons. First, China’s current surplus has come down to 2.3% of GDP in 2012, comfortably below the 4% proposed by the US as a way of defusing tension over currencies. Second, the RMB has appreciated 3.4% against the USD since Aug12; the most among Asia ex-Japan currencies. Over the same period, the RMB has strengthened 6.6% in nominal trade-weighted terms.

Softening tone on the RMB

The US also showed a softer stance by supporting “the inclusion of RMB into the SDR basket when it meets the IMF’s existing inclusion criteria”. The SDR currently comprises the dollar, euro, yen, and sterling. It is an international reserve asset created by the IMF to supplement its member countries’ official reserves. The IMF completed its last SDR review in 2010 and did not open it up to RMB since it was not used widely enough.

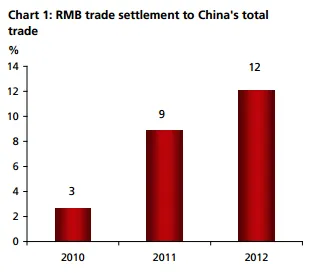

But the international use of the RMB has risen a lot since then. In 2012, the proportion of China’s trade settled in RMB quadrupled to 12% from 3% in 2010 (Chart 1). RMB-settled inward and outward direct investment ballooned 180% and 50% respectively last year (Chart 2). The outstanding dim sum bond market also experienced multi-fold growth. More importantly, overseas central banks also show increased appetite for

the currency. Australia, Nigeria, Chile, Thailand, Brazil, and Venezuela have already planned to purchase China’s sovereign bond.

Expanding opportunities for US institutions

With the US less focused on the exchange rate, other issues have come to the fore; including the participation of US banks in RMB cross-border business. In 1H13, RMB cross-border business conducted by banks in Shanghai exceeded RMB370 bn. According to a top-ten list published by the Shanghai branch of the People’s Bank of China (Chart 3), Chinese banks were among the topthree collectively processing RMB175 bn (47% of the total); followed by a UK andSingapore-based bank. Only one US bank is included and ranked second to-

last on the list. As the RMB is being increasingly used in global transactions, it is clearly a disadvantage for US banks to lag behind their global peers in RMB business.

China acknowledged US concerns and pledged to “welcome the participation by qualified locally-incorporated foreign banks in RMB settlement of cross-border trade and investment transactions”; and will “actively consider

reducing the waiting period for a foreign bank branch to apply for an RMB license”. That will lubricate US banks’ RMB business, while we are lukewarm on the prospects for any rapid growth given the low RMB adoption by the US corporates. According to SWIFT, 95.5% of the payments between the US and China/Hong Kong is still performed in USD, with only 0.3% in RMB. Without a doubt, a number of challenges is needed to be overcome before the RMB use in China-US trade can take off. That includes the USD-only invoicing systems and corporates’ inertia use in the USD – a traditional and primary international currency.

Developing the mainland bond market

With respect to financial market liberalization, China agreed “to encourage investment by foreign and domestic institutional investors in government bonds and government bond futures”. Doing so not only allows foreigners to capitalize on the China’s growth story, but also advances the mainland bondmarket. At present, commercial banks are the largest investor group in theChina’s government bond market – holding 69% of the outstanding papers(Chart 4). Among them, national commercial banks and city commercial bankshold 57% and 7% respectively. Holding by foreign banks is as low as 1.6%.

The dominance of local commercial banks in the bond market reflects theunder-development of direct financing via China’s capital markets. First, indirectfinancing provided by commercial banks drives the growth of the depositbase through the money multiplier. The resulting large liquidity held by banksdrives banks’ asset allocation to the bond market.

Introducing a broader and multi-layered institutional investor base will transform the mainland bond market into a more balanced demand structure. It will in turn become more competitive, transparent, and efficient in allocating capital to the economy. Alongside other initiatives such as encouraging corporate issuance and developing a stronger regulatory framework, a deeper and broader domestic bond market can thus be formed. This is a crucial condition for China’s capital account liberalization as well as RMB full convertibility.

Fostering an open and fair investment relationship

On the investment front, China announced its intention “to pursue a bilateral investment treaty with the US that will cover all phases of investment, including market access, and sectors of the mainland economy”. In particular, China committed to further open up its services sector; including through the establishment of the Shanghai Free Trade Zone pilot. While detailed guidelines are forthcoming, the pilot is expected to permit foreign enterprises to compete on the same terms as Chinese firms across a wide range of services sectors.

China also identified the e-commerce and commercial factoring sectors as areas for future liberalization to foreign investment. Equally impressive, China pledged “to ensure that enterprises of all forms of ownership have equal access to inputs, such as energy, land, and water”. The ultimate goal is to develop a market-based mechanism for determining the prices of those inputs.This will help level the playing field for foreign enterprises competing with Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that often pay below market cost for their inputs.

For the US, it “commits to maintain an open investment environment for Chinese investors, including SOEs, as with investors from other countries”. That demonstrates the US’s eagerness to improve its relationship with China. In the past, Chinese direct investment was often viewed with suspicion because it was dominated by SOEs. These were considered a threat to competitive markets and, occasionally, to national security. Consequently, though China was the largest investor in developing economies in 2010 and 2011, it represents less than 2% of the US’s total stock of inward investment. According to the Heritage Foundation, China has ploughed about USD50 billion into the US during 2005-2012. But over USD200 billion-worth of potential deals have fallen through due to political opposition and regulatory obstacles.

Political obstacles mainly targeted large M&A deals in sensitive industries, such as oil and gas, infrastructure, and high-tech industries (i.e., CNOOC’s failed bid for Unocal in 2005; Huawei’s unsuccessful attempts to acquire 3Com in 2008 and 3Leaf in 2010). Encouragingly, the share of private firms is growing. Investment made by non-SOEs accounted for 9.5% of China’s ODI in 2012, compared with less than 4% in 2010. As the role of private sector grows, US suspicions may gradually subside. China’s ODI would be even greater if the US was to become more hospitable towards mainland SOEs investment.

Mutual cooperation

In general, the dialogue should receive a guarded welcome. On one hand, China’s commitments indicate the new government’s determination to carry out market reform vigorously in spite of strong local resistance. On the other hand, unlike previous meetings, which were highlighted by Chinese concessions, this dialogue emphasized the importance of promoting a comprehensive mutual beneficial China-US economic relationship. Based on the commitments affirmed by the two sides, some concrete steps could be taken before the next Strategic and Economic Dialogue.

Advertise

Advertise