Why raising bank capital requirements will help the global economy

By Moorad Choudhry“Basel III” is familiar as the outcome of the financial crash of 2008. Western governments demanded almost instantaneous reaction to the bailout of some of its largest banks (no Asia-Pacific bank had to be nationalised) but it was the entire global economy that ended up with the higher capital and liquidity requirements associated worldwide with the name of a small town in Switzerland. And now the world’s banks have to gear up for these more onerous demands of the regulator.

But the banking lobby has been fighting back ever since. While the requirement to increase levels of bank capital is a natural reaction to a banking crash, bankers themselves have been arguing that raising capital levels to those demanded by Basel III would be detrimental to bank lending growth. The Institute of Economic Finance, chaired by Josef Ackerman (until last year the CEO of Deutsche Bank) claimed in a report that higher capital requirements would reduce global output by over 3%. That is some contraction!

This might seem perverse to the layman. After all a bank’s equity base – its assets minus liabilities – is what it has to protect it from bankruptcy if its assets start defaulting, so naturally Regulation 101 suggests that the more capital a bank has, the safer it will be in the event of economic downturn. So everyone should see the sense of it, yes?

Not so. The chart shows global bank capital levels since the 19th century, and we see clearly that capital levels have been headed downward ever since. Only the 2008 crash reversed this trend. (See Figure 1)

Bankers themselves have been shouting loudly from the rooftops that raising capital levels will reduce what they have available to lend into the economy, and will also increase their cost of funding, which will be hurtful to corporate and retail customers.

Both are spurious and fallacious arguments. It is important not to confuse leverage and return on equity (that is, profit) considerations with the absolute capital base of a bank. A bank can lend as much as it raises in deposits, and theoretically this amount is unconnected with what capital it holds. In fact it can lend more than what it raised in deposits, covering this shortfall from the interbank market.

The idea that raising capital requirements means a bank will have to “set aside” more capital rather than lend it out is a nonsense. A bank’s capital base shouldn’t be invested in risk-bearing assets anyway. What bankers mean when they say this is that their leverage ratio will have to come down, which results in a lower level of relative lending to their capital base. But the absolute level of loans need not be affected.

What about the cost of funds? Bank equity is the most expensive part of its liability structure, yes, but a higher equity base will lower leverage and make the bank a safer and more attractive option for shareholders and creditors. The cost of the bank’s debt – and thereby its weighted-average cost of funds (WACF) – would then decrease as its credit rating improved, so in fact the bank, and then its customers, would benefit in fairly short order as the WACF lowered.

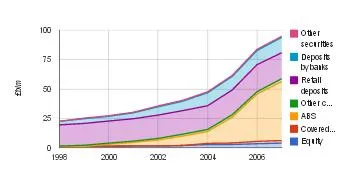

A safer banking system arising out of higher capital levels means more confidence in the sector, lower funding costs and more loan origination as banks raise more deposits. It’s actually a very good thing in any economy. Time to brush aside these tired and predictable objections from the bank lobby and move full speed towards reversing the long-term trend illustrated in our chart. (See Figure 2)

Advertise

Advertise