The implications on global 'currency wars' on Asian banks

By Martin SmithThe growing trend of central banks around the world to stimulate economic growth by instituting quantitative easing is having the effect – either intended or unintended - of rapidly depreciating major currencies such as the Japanese Yen, Chinese Yuan, US Dollar and Euro.

Asian Banks have been buffeted over the past two decades by the Asset Price Bubble of 1997, the Dotcom Crash and the Global Financial Crisis, but how well are they prepared to cope with an all-out ‘Currency War’ on a scale we have not seen since the 1930s?

A ‘Currency War’ is not a new concept, but the tools by which central banks, regional banks and businesses can cope with volatile foreign exchange movements have advanced greatly. The term itself was coined by the Brazilian Finance Minister Guido Mantega in September 2010 in opposition to the second round of Quantitative Easing (QEII) by the US Federal Reserve.

Global interest in Japan’s recent ‘Abenomics’ stimulatory measures and the G7 group of nations’ attempts to quell mounting concerns has piqued the interests of financial analysts in the “Currency War” scenario.

To encourage more liquidity, lending activity and business confidence, governments of the world’s largest and most influential economies have repeatedly purchased bonds in order to increase domestic money supply. This naturally devalues the domestic currency, causing exports to become cheaper, imports to become more expensive and a desired short term boost to economic activity and GDP growth.

Unfortunately the magnitude and prolonging of the Great Depression has been directly attributed to ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ policies similarly imposed by governments of that time.

The common reaction to rapidly falling currencies is to punish countries taking advantage of cross border capital flows in the form of higher tariffs, excises and barriers to trade. In an already suppressed lending environment, illustrated by China dropping its central bank rates over worries of a global economic slowdown, it is important for Asian banks to secure dependable sources of funding and not be exposed to international money market shocks resulting from currency devaluation fall out.

Asian banking stability is directly threatened due to current deposit funding and debt ratio changes. The lessons of the GFC are not long forgotten by households and businesses, reflected in increased levels of savings and reduced leverage all across Asia.

Weakening loan demand and intense competition for deposits and loans between Asian banks has contributed to a cautious, vulnerable banking environment that is ill equipped to deal with the array of macro complications a full scale global currency war would pose.

Businesses that hedge their currency exposure are also adversely affected by increased volatility and speculation in manipulated foreign exchange markets. A currency war raises the risk in sourcing credit from abroad, causing a contagion effect of illiquidity that directly hampers international trade.

Asian banks more than ever must provide strong, flexible currency management solutions for their customers in order to maintain current business, but more importantly gain new prospects from banks not prepared for the ensuing risk.

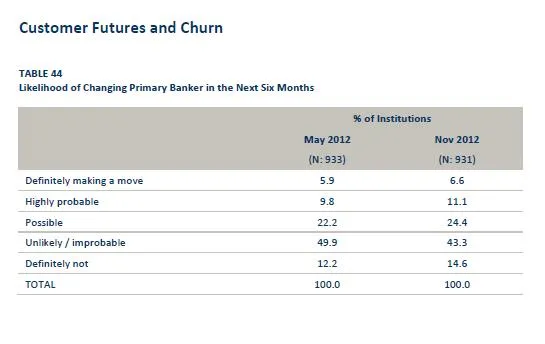

The latest East & Partners Asian Institutional Transaction Banking Report clearly shows the rise in the likelihood of customers changing their primary banker in the next six months:

See Figure 1.

In the second half of 2012 the percentage of customers definitely making a move or considering a new primary banker in the first half of 2013 rose from 37.9 percent to 42.1 percent. With these figures in mind it is essential Asian banks incorporate future orientated customer service and technology innovation policies to prevent rising customer attrition rates, and attract new business in a highly competitive market about to be squeezed further with unique ‘Currency War’ tribulations.

Asian central banks have over USD5 trillion of foreign currency reserves at their disposal should they need to stabilise the financial sector by supplying local or foreign currency. That should go a long way to ensuring markets have enough liquidity, especially when these reserves can be bolstered by other regional defences such as ASEAN’S “Chiang Mai” reserve pool, which is poised to double in size to USD240 billion.

Swap lines with the US Federal Reserve could be an important source of liquidity for those suffering an acute dollar shortage. They proved important for Hong Kong, South Korea and Singapore during the Lehman crisis and could be again for more vulnerable countries such as India or Korea.

Advertise

Advertise